Courtesy of the CDC

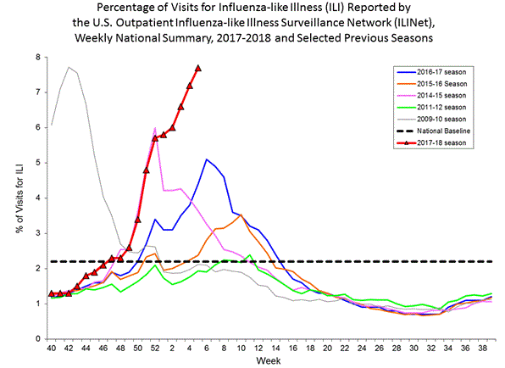

Influenza is back among us—and with a vengeance. We are just about at the midpoint of the flu season, and already experts are calling it the worst epidemic since 2009, when a new (H1N1) influenza strain appeared, resulting in the deaths of more than 12,000 Americans.

Now, not all “flu-like” illness is caused by the influenza virus. Several other viruses, including respiratory syncytial virus and adenovirus, can cause similar respiratory and nonrespiratory symptoms and signs. Laboratory-confirmed cases of influenza, though, are very common this winter season.

Influenza comes in three “flavors”: A, B and C. Type C causes sporadic cases, and usually escapes specific diagnosis unless there is a concurrent study of respiratory pathogens going on. Type B usually causes influenza in closed populations such as boarding schools and military boot camps, producing generally mild cases of the disease.

What Makes Type A Influenza Deadly

Type A is the real villain. Infection with this type often leads to epidemics and worldwide pandemics, sometimes with extremely high mortality. It is believed that some 40 million deaths were caused by influenza Type A in the period between 1918 and 1921. This year we’re facing two strains of Type A, and maybe a bit of Type B.

Influenza deaths seem to arise from two main features of the infection. One is the formation of a so-called hyaline membrane, which coats the lung’s alveolar surfaces and essentially suffocates the patient.

Another complication is called “cytokine storm”—the overexpression of a normal immune response to infection. This is the elaboration of chemicals called cytokines, which are usually a stimulus to immune function but can, when overexpressed, lead to death. This latter mechanism is thought to have been responsible for the high mortality in 1918 among young adults. Fortunately, the current strains circulating seem less virulent than the 1918 version.

A Vaccine Mismatch?

An interesting feature of this year’s outbreak is the apparent low protective effect of the influenza vaccine. Anecdotally, at Montefiore and elsewhere, many of the people who have presented to medical facilities with confirmed influenza have already received the vaccine. Overall efficacy appears to be 10 to 36 percent, when it is usually 50 to 75 percent effective, according to the latest statistics from the CDC.

Each year, scientists predict which flu vaccine is needed based on the most recent virus outbreaks in Russia and China, the nations where most pandemics start. The most common cause of low effectiveness is a mismatch between the virus strains in the vaccine and those actually causing the disease in a given year. However, this year there is a good match, and the reasons for low protection have not yet been ascertained.

The Need for Vaccines

Vaccines are directed against two virus surface proteins: hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. The first helps attach the virus to respiratory epithelium (the tissue lining the respiratory tract); the second helps detach newly produced virus particles from the surfaces of cells so they can go on to infect other cells. Antibodies to these two surface elements are the main forms of protection against infection. However, influenza virus is almost unique in being able to alter these elements from year to year, which means we require annual vaccination for optimal protection. It is the varying hemagglutinin that determines the magnitude of the cytokine response. The hemagglutinin in the 1918 swine influenza virus has been identified and found to be a superinducer of cytokines.

Many researchers, including some at Einstein, are searching for the holy grail of this disease: an antibody against an influenza virus antigen that does not vary from year to year—a universal flu vaccine.

In the meantime, vaccination, even at this late date, is your best bet for avoiding influenza. A drug called oseltamivir (Tamiflu®) is also somewhat effective in preventing flu when taken at the time of exposure, and in truncating illness and the spread of the virus when taken within 48 hours of the start of symptoms. Some medical professionals have recommended nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to ameliorate the cytokine storm. The Centers for Disease Control also recommend a second vaccination for older patients with underlying cardiorespiratory disease when the season extends into spring.

And please, if you do come down with influenza, stay home to diminish its spread to others.