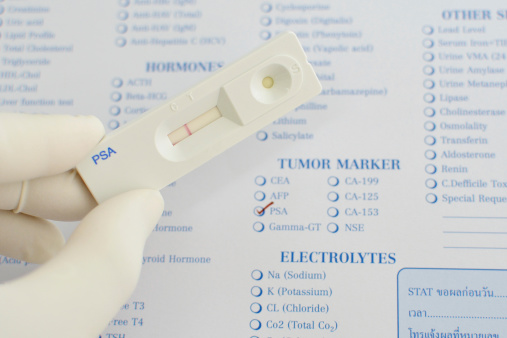

EDITORS’ NOTE: In October, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) openly questioned the value of PSA tests to screen for prostate cancer, saying there is insufficient evidence to suggest the PSA blood test is useful as a screening method and may do more harm than good.

The recommendation has created lingering questions for the estimated 30 million men who undergo PSAs every year.

This week, we present Felise Milan, M.D.’s view of the controversy. Her thoughts follow:

The concept of screening for cancer is very attractive—even seductive—for both physicians and patients. What could be better than a test that finds a cancer early and prevents unpleasant complications or even death?

For many years, this was the lure of the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening test for prostate cancer. Despite mounting evidence that the PSA test was neither sensitive nor specific enough as a screening test, that it failed to reduce mortality rates significantly and resulted in serious complications, patients requested it and doctors eagerly ordered it up.

Sociologists have long known that for many physicians, anecdotes have a much more powerful effect on decision making than scientific evidence. These factors include reporting bias, confirmation bias and the fallibility of human memory, just to name a few.

Over more than two decades, academic scholars have marveled that despite strong evidence discounting its utility, PSA screening remains so common. Probably the most knowledgeable of these is Harvard Medical School professor of medicine Michael Barry, M.D., past president of the Society for Medical Decision Making, whose arguments are well laid out in an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Evidence against PSA screening was set aside in favor of anecdotes for too many years. After all, when former New York Yankees manager Joe Torre tells the people of the Bronx that a PSA saved his life and will save theirs, who can argue?

However, there are also many stories of men who have undergone PSA screening and suffered significant and life-changing complications from treatment of cancers that might or might not have actually caused them harm. Some of these stories, as well as a balanced discussion of the PSA debate, appeared in an October 2011 article in the New York Times Magazine.

This year some very brave physicians and scientists on the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) made the much-overdue recommendation against PSA as a screening test for prostate cancer. The diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer are big business, so the pressure on this committee not to make this recommendation was formidable. Kenny Lin, a committee support team member, resigned in protest after a November 2010 meeting was cancelled when it was leaked that the group was going to vote on making this recommendation.

This USPSTF article systematically lists all the studies showing that PSA testing fails to reduce mortality from prostate cancer. The article adds that testing is associated with potential harms, including serious infections or urinary retention in about 1 of 200 men who undergo prostate biopsy as a result of an abnormal screening test result, and that it is also likely to result in overdiagnosis in as many as half of all cases. The overtreatment of such low-risk cancers exposes men to unnecessary and unwelcome harms such as erectile dysfunction and incontinence.

Stories of all those men who have been “saved” by having a PSA screening test are as seductive as Sirens. But it’s our job as physicians to be scientists who make decisions based on evidence, not on anecdotes, no matter how compelling the story or its teller.

Comments on this entry are closed.

May I suggest you have missed a critical point in your argument. Evidence is only half the battle. People didn’t stop believing the universe revolved around the earth or that the world was flat for a very long time, in spite of the evidence.

The real lesson from this is that scientists, physicians and many others need to be much more aware that:

a) Stories are incredibly powerful and have the capacity to change and influence behaviour

b) The power to act (and make decisions) is in the hands of the patient, not in the hands of the physician or scientist

c) Scientists must acknowledge that it is not enough for them to know, they must also work on communications, creating relationships and demonstrating leadership

d) A key aspect of leadership communication is the ability to tell stories

People communicate and form relationships through stories. There’s no point battling that aspect of the problem, instead you should be using this knowledge to improve your communication of the evidence and your creation of trust that will lead to the change you advocate.

All the best. geoff