The third year of medical school is the clerkship year, which means it’s learn-to-wear-your-white-coat-convincingly year, and figure-out-where-the-best-late-night-food-options-are year. But it’s also try-to-understand-what-kind-of-doctor-you-want-to-be year, and that decision is a stressful one.

Here’s what you should know about this decision: It’s not actually about the organ systems you like to think about. (Very few people go into medicine really wanting to talk just about the liver all day. It’s a really great organ, but you know what I mean.) It is not—despite what many people will want you to believe—about being a nice person (pediatrician) vs. not nice (all surgical specialties); every physician should be personable, though every field has outliers.

In the end, I think this career choice is usually about temperament, and finding out what you enjoy or what you need to avoid. For me, it was mostly about two things: the level of medical severity and urgency I like to deal with and my comfort level and skill in conducting procedures.

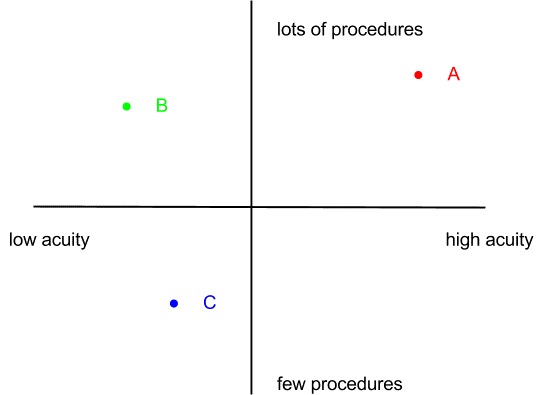

Once you have those two things that you feel define what you do and don’t enjoy, and if you are a nerd (and frankly, most of us qualify), then you can set up a set of axes. This, for example, would have been mine, circa 2002:

When I started med school, I was planning to enter a low-illness-severity or low-acuity (serious or urgent) field; I didn’t think I’d like taking care of high-risk, critically ill medical patients. I envisioned being a general pediatrician or a child psychiatrist. That would have put me somewhere near dot “C” above.

But it turns out that wasn’t who I was. From my first rotation in surgery, I loved doing procedures. Realizing how much I enjoy working with my hands to fix people’s bodies remains one of the great surprises of my life. That was a helpful surprise, because it knocked out two quadrants of specialties. All other things being equal, that could have placed me solidly near dot “B” above—maybe an ophthalmologist, or an ENT.

Surprise! I like medically complicated patients, and I like having a bit of urgency to the conditions I address. This quadrant, near dot “A,” is for some of us who may exhibit just a little bit of the tendency to be what one of my attendings used to call “adrenaline junkies.” So “A” might be for the trauma surgeon, or the critical-care intensivist, or, in my case, the maternal fetal medicine (MFM) specialist.

This meant I ended up thinking very seriously about becoming an ICU doctor, as well as about becoming a general surgeon or an interventional cardiologist.

Part of why I love to talk about this graph with med students now is that, once you figure out what works for you, the graph shows you that there might be many ways to get to the area around the right dot. In the end, there are a lot of career choices that can take you to a career that you will enjoy and find satisfying.

Your graph will likely look different. It might include other axes, such as “allows for a research lab career” or “does not require me to stay up late at night ever again.” But during the crazy I-have-to-figure-out-the-rest-of-my-life-right-now year that third-year clerkships can feel like, this was a helpful framework for me.

In the end, I became an MFM specialist; I operate frequently, and take care of complicated, medically ill patients—a solid dot “A” job—and I love what I do. But during that what-if-I-make-the-wrong-choice year that is the third year of medical school, it helped me think about how there was, quite likely, more than just one right choice. I hope this will help you, too.

How did you make your physican career decision? Tell us in the comments below.

Comments on this entry are closed.

Interesting insight into medical career planning for those who are not in the loop. However, everyday experience of patients seems often to indicate that doctors chose their specialty applying another dimension that’s missing in the above quadrants:and it has to do with money. That doesn’t go for everyone and you convincingly describe a different path of reasoning. And certainly people like medecins sans frontieres etc. are above any such speculation. But the doctors whom one meets in private practice sometimes seem to suggest otherwise.

I have yet to meet a doctor who truly goes into medicine just for the money.. if that were true, they wouldn’t have spent 200k on an education.. There are easier ways to make a lot of money that don’t require call hours and dealing with the politics of medicine.

This is very helpful. I have seen far too many medical students choose a specialty based on how nice the attendings are or how well they fit in on a particular rotation. I am constantly saying, ok, so our xxxx’s are jerks, but if that is what appeals to you, don’t rule the specialty out.