When people hear the term “MRSA,” they usually look panic-stricken and scared. Many people know this abbreviation from stories on the evening news or in the newspaper describing the terrible infections MRSA can cause in hospitalized individuals.

Most physicians, regardless of their specialty, are also aware of the importance of this organism in the hospital, especially in the Northeast and particularly in New York City, where it is quite prevalent. However, what most physicians and patients don’t realize is that MRSA has become part of our daily lives.

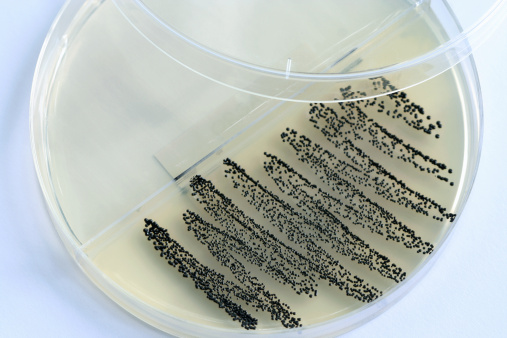

In our community here in the Bronx, MRSA, the antibiotic-resistant (or, more specifically, the methicillin-resistant) strain of Staphylococcus aureus, accounts for approximately 50 percent of all S. aureus that is cultured from patients outside the hospital (usually from a wound that is swabbed by a doctor in the office). When I share this statistic with patients and practitioners alike, they are invariably stunned. There is a misperception that these bacteria cause disease in the hospital, but that people in the community are not at risk.

A recent illustrative example is the experience of a close friend of mine. When she went to her dermatologist’s office because of a painful swelling of her skin, the doctor took a culture of the area and gave her a prescription for an antibiotic to treat a skin infection. The following week she returned to the doctor, who told her the culture had grown MRSA. The doctor said, “Where did you get this?” My friend was frightened, and called me right away in a panic. She was shocked to hear that, like many other healthy people in our community, she had MRSA in the normal mix of bacteria living on her skin.

The mere presence of MRSA on a skin culture does not always result in a symptomatic infection. MRSA, just like methicillin-susceptible S. aureus, exists on the skin of many people who are otherwise healthy, and never causes a problem. However, in the event of an injury to the skin, even something as minor as a scratch, MRSA can easily cause a skin and soft-tissue infection. It is likely that such individuals either were exposed to antibiotics, resulting in the de novo development of MRSA, or had contact with a person or surface containing MRSA. This explains why there have been outbreaks of MRSA skin infections in young, healthy people who participate in sporting activities with close skin-to-skin contact, such as wrestlers and others who share mats or gym equipment.

So what can we do to combat this problem?

Community-acquired MRSA is the inevitable result of decades of overuse of antibiotics, mostly for viral upper-respiratory infections that don’t require antibacterial drugs. Though most practitioners, and even some patients, are aware of the problem of emerging antibiotic resistance and “superbugs” caused by the indiscriminate use of antibiotics, many assume that this is a problem confined to the hospital wards.

The prevalence of MRSA in the community challenges that assumption, and illustrates the need for judicious antibiotic prescribing in all settings, including the outpatient office. It also underscores the importance of hand washing and cleaning of communal areas, shared equipment in fitness centers and similar environments. We strictly adhere to infection-control practices in the hospital setting, but often forget that those principles can be effective in preventing disease in our everyday lives.

By raising awareness of the benefits of good hygiene practices and antibiotic stewardship everywhere, not just in the hospital, we can help prevent further drug-resistant bacteria such as MRSA from emerging in our community. We can also improve care by reminding practitioners that MRSA isn’t just a “hospital” problem anymore.

Medical personnel should be aware that any patient who comes for an office visit with an infection could have MRSA, and this should be considered when investigating the problem and choosing a therapy. Specialists in infectious diseases can assist with choosing an antibiotic regimen. Of particular concern, MRSA can be harbored asymptomatically in one area of the body and act as a reservoir for the spread of the bacteria to another area of the body or to another person. As a result, specialists may even attempt to “de-colonize” the patient by eradicating the MRSA through a combination of skin treatments and medications.

The scientific community is working on additional ways we can address the growing MRSA problem in the U.S. As our antibiotics lose their effectiveness, interest has developed in nonantibiotic therapies for infectious diseases. By harnessing the innate power of the immune system to fight drug-resistant infections through immunotherapy or development of vaccines that target specific microbes such as MRSA, we hope to add unique tools to our infection-fighting arsenal.

It will certainly take a multifaceted approach to tackle the problem of MRSA, but if we all remain vigilant, I’m hopeful that, over time, we can gain the upper hand.

*Patient circumstances and descriptions have been altered to protect patient confidentiality.

See related content on best practices in prescribing antibiotics at https://bitly.com/1bZ3x5Y

Comments on this entry are closed.

Could you please explain me if it is also possible for MRSA to cause a skin infection in case the person has been bitten by bed bugs?