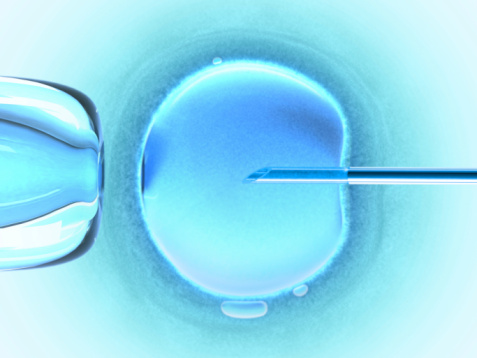

A recent article in the Wall Street Journal describes a couple’s decision to use preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) to see whether the woman’s embryos had the BRCA gene, a mutation linked to breast cancer. PGD enables embryos created by in vitro fertilization (IVF) to be inspected for a variety of genetic conditions, so that only those embryos that are unaffected will be transferred to the woman’s womb to achieve a pregnancy.

The article refers to PGD as “a controversial procedure” and profiles 34-year-old Katie Dowdy, who knew that she carried the gene herself though she had not had cancer. She expressed the wish that her two daughters (both born using PGD) would not have to worry about being at high risk for breast cancer.

The PGD Question

Is PGD controversial? And if so, why? Doesn’t it make perfectly good sense for couples at risk of having a child with a genetic disease to prevent that from happening? Although it is tempting to reply with an unqualified “yes,” several factors complicate the situation.

For some people, the use of PGD is unacceptable when it leads to the destruction of embryos, regardless of the severity of the genetic condition in question or the likelihood of its occurrence.

For others, the destruction of embryos is ethically preferable to termination of pregnancy when genetic diseases are detected by testing a fetus already implanted in the woman’s uterus.

Still other people are prepared to accept the destruction of affected embryos when the genetic condition is severely disabling or would be fatal within a few years after birth, but not for milder conditions or those that appear much later in life.

When IVF Adds Risk

Then there are the risks to the woman undergoing PGD. When a couple has been diagnosed as infertile and decides to proceed with assisted reproduction, the risks to the woman of taking the necessary hormones and undergoing retrieval of her eggs for IVF are an essential part of the infertility treatment. The complications risked are rare, but include discomfort, infection, multiple pregnancies and even miscarriage.

For women who would otherwise conceive normally, these are additional risks. Nevertheless, this is a decision for the woman to make for herself, given the provision of full information. A woman should be free to decide that the benefits of having a healthy child through the use of PGD outweigh the added risks to her of the IVF procedures.

“Playing God” and PGD

Still, some concerns expressed about the use of PGD can be readily dismissed. Ms. Dowdy reportedly said that her husband initially “worried about playing God.” While it may be well intentioned, this old canard about the use of medical technology should be laid to rest. Everything that today’s modern medical technology can offer represents something other than what would occur if nature were left to take its course. Surgical interventions, ventilators, medications to control severe hypertension and cesarean sections save lives or sustain health, and could just as readily be subjected to the “playing God” criticism. PGD is no different.

Another unwarranted concern mentioned in the article: “Critics fear genetically vetting embryos can be used to create so-called designer babies.” The mistake here lies in equating prevention of genetic disease with enhancement of normal physical attributes, which is what these critics presumably fear.

Creating a Gender Imbalance

One additional controversial point about PGD is its use in sex selection of the embryo. Twenty years ago, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) issued a report stating that while preimplantation sex selection is appropriate to avoid the birth of children with genetic disorders, it is not acceptable when used solely for nonmedical reasons.

More recently however, the professional society softened that claim, allowing that it is not unethical to use PGD for couples seeking “gender variety” or “family balancing.” The ASRM still cautions against widespread use of PGD for sex selection of offspring. The chief worry is that enabling couples to choose the sex of their child will lead to an imbalance in the sex ratio, something that has already occurred in some Asian countries, especially China, where a preference for male offspring prevails. However, evidence from studies in the United States has revealed that with the exception of some ethnic groups, couples in general have no gender preference for their offspring.

PGD is by now a well-established procedure in reproductive medicine. Although its use may continue to give rise to some ethical controversy, the benefits to couples and the children they produce outweigh the potential negative consequences feared by some.