One typically thinks of advances in medical science and technology as having unalloyed benefits. The ability to cure illness, the mitigation of pain and the possibility of making diagnoses that are more accurate are some of the uncontroversial results of medical progress. Yet as a new study of vegetative states demonstrates, such advances can raise ethical quandaries for physicians and the families of patients diagnosed as vegetative.

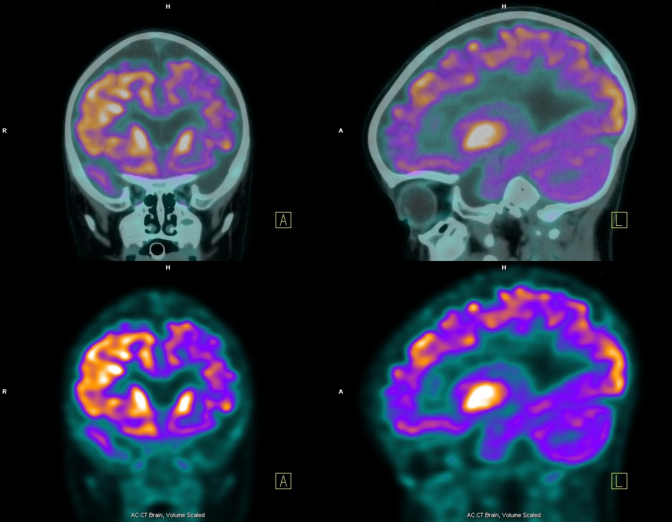

The study, conducted in Belgium and published in the British medical journal Lancet, showed that using the brain-imaging technique known as positive emission tomography (PET) provided a more accurate neurological assessment than other techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging. The assessment provides more information about “minimally conscious” states, originally thought not to exist in such patients. Evidence from recent research had demonstrated the existence of minimal consciousness in vegetative patients, but without the details that emerged in the Belgian study. The latter revealed that not only do patients who are minimally conscious have some level of awareness or responsiveness, but they may also have some chance of improving and regaining higher levels of consciousness.

More Information, More Quandaries

Why does this new research pose ethical quandaries? Aside from the acknowledgment by a researcher in the Belgian study that the diagnostic technique is not ready for routine use, a bigger problem is the uncertainty in its ability to predict significant improvement or recovery. This can lead to “false positives”—diagnoses that show minimal consciousness and a prospect of improvement in brain function when that will not occur. This situation produces uncertainty among medical experts and families who are hopeful that their loved ones will recover cognitive function. As the Belgian researcher stated, “We shouldn’t give these families false hope.”

In such circumstances, physicians and families may be unlikely to remove life supports even after significant time has elapsed, creating anguish about whether and when to “pull the plug.” Until recently, the problem of uncertainty was that of “false negatives”: diagnoses that patients in a vegetative state had no consciousness at all when, in fact, they may have been minimally conscious. With the new study, uncertainty about eventual improvement looms as a barrier to timely decision making. And lingering uncertainty often is worse for people who have to make decisions than receiving a bad but definitive prognosis.

Some controversy still exists regarding the ethics of removing ventilators or artificial feeding from patients diagnosed as having no chance of recovery. Although families’ willingness to have life supports removed from their relatives is now more common than refusal, opposition remains strong among members of some religious groups. The new evidence may lead to changes in families’ agreement to terminate life-sustaining treatment. And while the use of PET scans for this purpose is not ready for prime time, as further studies confirm the results people may begin to demand this diagnostic technique on a routine basis.

Should Advance Directives Be Updated?

Advance directives (formerly called “living wills”)—instructions people make while fully competent about what they would want to happen if they were to lose decisional capacity—have been made by only a minority of people in the U.S. Yet among those of us who have executed such documents, the question arises: Should we consider revising them in light of this new research? The standard wording in some advance directives says: “I direct that my healthcare providers and others involved in my care provide, withhold, or withdraw treatment . . . if I become unconscious and, to a reasonable degree of medical certainty, I will not regain consciousness.” (This choice not to prolong life appears in the New York State template for the advance directive.) Should such standard wording in forms provided by states now be amended to include mention of “minimally conscious states”?

The other option on the form—the choice to prolong life—says: “I want my life to be prolonged as long as possible within the limits of generally accepted healthcare standards.” If and when the use of PET diagnoses of vegetative states becomes an accepted healthcare standard, will people who make advance directives change their decisions?

These questions lie in the future. But as many in the field of bioethics urge, it is best to begin thinking about and discussing future medical scenarios before they are upon us.