In my work as a bioethicist, I have very rarely taken an “absolutist” position regarding the use of a biomedical technology. But when I read an article titled “Chinese Scientists Edit Genes of Human Embryos, Raising Concerns,” my reaction was that this should not be done. I am not alone.

The technique mentioned enables genes to be altered in every cell of a human embryo so that all changes would be passed on to future generations. Prominent researchers spoke out in scientific journals urging that such work on human embryos be halted, “at least until it could be proved safe and until society decided if it was ethical,” the New York Times article stated.

Clear Intentions, Poor Results

Clear Intentions, Poor Results

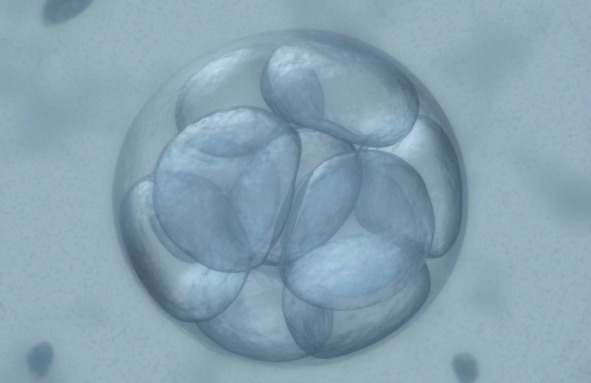

It is clear that the Chinese scientists did not plan to produce a baby with altered genes using this technique; they used defective human embryos that would not have been transferred to a woman’s uterus for gestation. However, the experiment itself was a spectacular failure in achieving its intended aims. None of the 85 embryos whose genes were edited fulfilled two basic criteria: precisely altered genes in every cell with no accompanying DNA damage. Either the genes were not altered or the embryos died.

Not All Genetic Material Alterations Are Equal

The alteration of every cell of a human embryo is vastly different from the replacement of diseased mitochondria in a woman’s egg—a technique I wrote about on this blog two months ago. In that genetic alteration, less than a tenth of one percent of the genome would be affected, and those effects are not ones that determine the individual characteristics that make us what we are.

Imagining the Consequences

In the DNA editing attempted by the Chinese scientists, every cell in an embryo would be altered in the attempt to eradicate a heritable disease. We can only imagine what could go wrong. Genes that should not have been altered might be altered irrevocably. Collateral damage could occur to some or all genes. And any devastating results would continue for generations.

One of the world’s leading experts, Dr. Rudolf Jaenisch from M.I.T., even questioned the applicability of the technique. He points out in the New York Times article that because of the technique involved, normal DNA would be forever altered needlessly.

A Science-Ethics Gap

The two criteria proposed in the article by the eminent scientists are problematic: “until it could be proved safe and until society decided if it was ethical.” We have ample experience of how difficult it is to prove that a drug, device or biomedical technique is safe. The best we can ever get is evidence, albeit sometimes good evidence. Think, for example, of all the drugs and devices taken off the market once they have been “proven” safe and approved by the FDA. Sometimes the harmful effects of a product or technique are not discovered until long after it has been in use.

In the case of diethylstilbestrol (DES) given to pregnant women to prevent miscarriages, the effect showed up in the next generation in their daughters, who were at increased risk of cancer of the vagina or cervix. Furthermore, even when a medical technique is demonstrated to be safe in the best hands—knowledgeable scientists conducting research—the possibility of human error can be considerably greater when a technique enters the clinical realm and is carried out by practitioners with less knowledge and little experience.

Society’s Failures

As for society deciding if the technique is ethical, what method do the scientists calling for a halt have in mind? A national referendum? A determination by elected representatives in Congress, some of whom have shown themselves to be either scientifically ignorant or patently antiscience?

One has only to look at the abysmal failure of “society” to agree on the ethics of abortion, contraception, the importance of vaccinating children and a host of nonmedical issues to conclude that seeking to obtain society’s agreement on what is ethical is an exercise in futility.

This is one of those rare instances in which I maintain that a line must not be crossed. Editing the genes of human embryos—or fertilized eggs—to eradicate a heritable disease should not be attempted.