What excites a scientist’s brain? Is it the next big breakthrough experiment that will save humanity? Is it the approval of the R01 grant that will guarantee another few years of life in the laboratory? No. According to a recent study from the University of Lübeck, in Germany, what really tickles a scientist’s brain is seeing his or her name as an author of a paper, preferably in a high-impact journal.

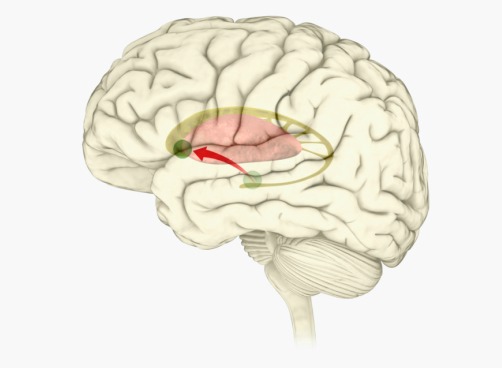

Research published in the journal PLOS ONE indicates that the same brain area (the nucleus accumbens, or NAcc) that is responsible for high-risk, high-pleasure-seeking behavior, such as drug addiction, lights up like the proverbial Christmas tree when that scientist’s name is listed as an author of a scientific paper in a top-ranking journal.

Research published in the journal PLOS ONE indicates that the same brain area (the nucleus accumbens, or NAcc) that is responsible for high-risk, high-pleasure-seeking behavior, such as drug addiction, lights up like the proverbial Christmas tree when that scientist’s name is listed as an author of a scientific paper in a top-ranking journal.

A lot has been said about the “impact” factor—how bad it is (or can be) for basic science and how it can foster data manipulation. Even so, the prestige and press coverage a high-impact journal brings with it are important parts of a researcher’s career.

Better than cash

The study compared the activation of the NAcc of 18 neuroscientists after seeing their names as authors on papers with varying impact factors (very high to low) to the activation after having varying amounts of cash promised to them. Surprisingly the authorship of even a low-impact paper evoked a higher activation of the NAcc than the biggest bundle of cash.

To understand this somewhat odd activation pattern, one has to keep in mind that in a world where the words “publish or perish” are an accepted, albeit worrying, reality, authorship of a high-impact paper increases the likelihood of grant renewals and opens up almost infinite tenure-track position possibilities.

Therefore, the authors argue, this specific activation represents an adaptive mechanism by scientists to today’s academic standards. In other words, the NAcc—one of the major hubs of the brain’s reward and pleasure center—is particularly activated when achieving publication, which in turn can be seen as currency in academic circles and directly affects a scientist’s career trajectory.

Scientific rewards and reactions

This means that following years of training in school and university, not only do scientists become experts in their chosen fields, but they also adjust their reward systems to adapt to their chosen lifestyles. High-quality bench science often leaves little time (or money) for outside activities that would activate the same reward circuits. Thus, with careers so focused on publication and little time to get their rewards elsewhere, scientists adjust their intrinsic reward centers to fit the demands of their jobs.

What this study also suggests is that the opportunity to get published is vital to keeping (young) scientists engaged with their careers. And if we want to make sure underrepresented groups are included in research institutions, it’s important to address biases and inequities found in how high-impact journals and others decide what to publish.

In the end, the fact that the reward system of scientists responds particularly well to high-impact publications, while interesting and nicely demonstrated, is not necessarily more surprising than the reward system of a football player who scores a touchdown.

Nonetheless, as with most sports, watching the event can be fun, and playing the game certainly is satisfying, but getting the chance to score is a unique thrill.