In November, while reading the first accounts of the association between the Zika virus and congenital microcephaly, I immediately thought of Sir Norman McAlister Gregg. And while thinking of Dr. Gregg and all that’s happened since he made his important observation in 1941, I hoped that we could learn from our past.

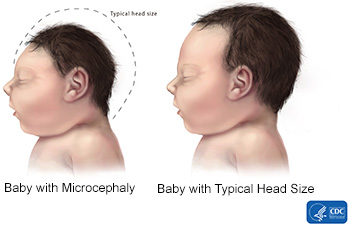

Image courtesy of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities

In the spring of 1941, Gregg, a pediatric ophthalmologist in Australia, realized that he was seeing a marked increase in the number of children who’d been born with cataracts. The numbers were striking: in past years, he’d seen an average of five to 10 babies per year with cataracts; in 1940 to 1941, he was seeing more than 10 times those numbers.

Though Gregg had no idea what was causing this increase, one day he overheard a group of mothers in his waiting room discussing the fact that they’d each had German measles during their pregnancies. This overheard conversation led him to question whether rubella might be responsible for their children’s problems.

Reviewing their case histories, Gregg found that 68 of the 78 infants with cataracts he’d seen during this period had been exposed to rubella during gestation. He also discovered that in addition to cataracts, many of these children had sensorineural deafness and congenital heart disease. In October 1941, he presented his findings in a paper, “Congenital Cataract following German Measles in the Mother,” at the Ophthalmological Society of Australia.

Understanding threats to the womb

Gregg’s observations were noteworthy for numerous reasons. Not only did his work introduce the concept of congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) as a specific entity, it marked the first time an environmental agent had been implicated in causing damage to a developing conceptus. Prior to Gregg’s paper, the prevailing view was that while in the womb, embryos and fetuses were impervious to damage from external sources. The concept of a virally induced congenital malformation syndrome opened the door to the possibility that other viruses (toxoplasmosis and cytomegalovirus), as well as drugs (thalidomide and Accutane), chemicals (methyl mercury) and environmental agents (radiation exposure), might also be harmful to developing humans.

In the years following Gregg’s observation, as rubella epidemics around the world left thousands of affected children in their wake, other features were added to the list first generated by the Australian ophthalmologist. Virtually every organ system can be affected.

CRS and autism spectrum disorders

It also became clear that the timing of the infection is important: if the infection occurs early, a miscarriage could result; if the embryo survives, damage can occur to the lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys, bone marrow, bones, endocrine organs and brain, as well as to the eyes, ears and heart.

The effect on the developing brain leads to the condition’s most tragic consequences. Children with CRS are often left with severe, lifelong intellectual disabilities. Prominent among these disabilities are autism spectrum disorders (ASDs). Following the epidemic in the early 1960s, Stella Chase and her colleagues at New York University reported “a strikingly high prevalence of autism in a population” of children with CRS. Her work pointed to CRS as one of the leading causes of ASDs in America in the 1970s.

The devastating neurological consequences of CRS left little doubt that a vaccine against rubella was needed. In 1969, after years of work, the first rubella vaccine became available in the U.S. In 1971, it was combined with vaccines for mumps and measles, which had been developed earlier in the 1960s, to become the MMR vaccine.

The MMR vaccine controversy

The effect of MMR on the incidence of rubella was rapid. In only a few years, this disabling disease virtually disappeared from the landscape. Most pediatricians who trained after 1975 have never seen an infant with CRS. The vaccine was almost a miracle.

But one person’s miracle can be another person’s calamity. In the 1990s, the prevalence of ASDs soared. Although the dramatic rise in reported cases was almost certainly due to healthcare providers having become more sensitive to the symptoms and signs of the condition, this explanation was not acceptable to many parents. For these people, a more satisfying explanation came in 1998, when Andrew Wakefield and his colleagues published a paper in the Lancet (“Ileal-Lymphoid-Nodular Hyperplasia, Non-specific Colitis, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder in Children”), which claimed that MMR was responsible for a new syndrome: autistic enterocolitis.

And so the vaccine that had been developed to prevent the leading cause of ASDs in the 1960s was now being blamed for fueling the “epidemic” of ASDs that occurred 30 years later. In the years following publication of Wakefield’s article, not a single researcher could duplicate his findings, but the lack of evidence didn’t matter: people who wanted to believe that their child’s autism was caused by MMR would not be dissuaded.

Is MMR’s past Zika’s future?

It took 12 years and millions of research dollars to begin to correct the damage done by Wakefield. But even after 2010, when a tribunal found that he had acted dishonestly and irresponsibly in his published research, and the Lancet retracted the 1998 paper, many people (including U.S. presidential candidates) have continued to believe that a link exists between vaccines and ASDs.

So in November, when I saw those photos of babies with small heads and read those first articles that linked congenital Zika infections with microcephaly, I believed I might be able to predict the future. I imagined that those small heads would prove to be only the tip of the iceberg for these unfortunate babies. In addition to microcephaly, they would be found to have brain malformations, neuromuscular and seizure disorders, intellectual disabilities, including ASDs, and an assortment of medical problems. The phenotype of what might be called Congenital Zika Syndrome would prove so significant, the suffering so severe, that researchers would band together to develop a vaccine. The vaccine, which would become universal in its use, would prove to be a huge success in stopping the epidemic. But in time, this miraculous vaccine would inevitably become the target of criticism, as people would come to believe that it itself was responsible for some new clinical problem.

I hope that as we enter the age of Zika, we can learn from our experience with rubella, that although the development of a vaccine to prevent the tragedy of CZS will prove life-saving, it’s almost inevitable that eventually, someone somewhere will blame this miraculous substance for causing one or another of the world’s ills. And when that happens, it’s imperative that we in the scientific community urge the public to reserve judgment until definitive proof can be found to either prove or disprove the claim. For as George Santayana said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”