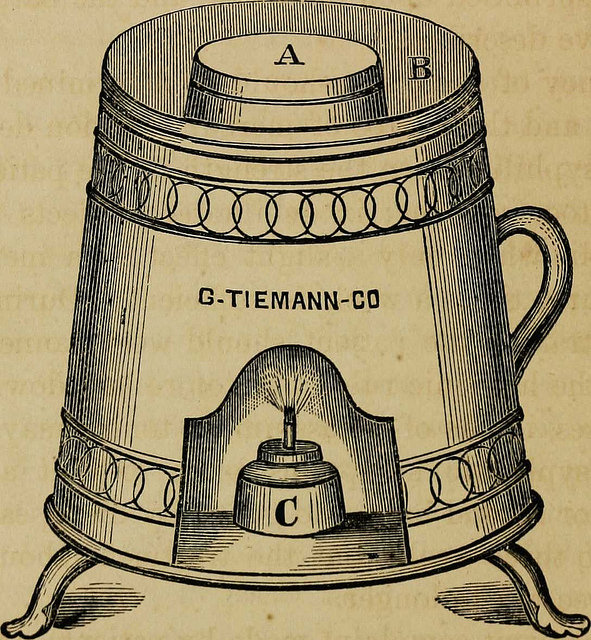

Illustration from an 1886 book, “The Pathology and Treatment of Venereal Diseases” of a device used to vaporize mercury, which was used to treat syphilis.

I first became interested in the history of medicine in middle school, when my seventh-grade science teacher lent me her copy of Microbe Hunters by Paul de Kruif. It is a small book, focusing on the struggles and discoveries of early microbiologists. Now, as I write this post, my own old, battered, well-thumbed copy sits in front of me. In our world of rapid innovation and emphasis on progress, what place do these stories hold? A group of committed historians, doctors and nurses gathered at the annual American Association of the History of Medicine conference in Minneapolis in April to explore the impact this field can have on our present understanding of health, disease and the medical professions.

Toward the end of the conference, this international group with varied and quite divergent interests came together for a lively discussion to consider the place of the history of medicine in medical education. Speakers emphasized the idea that a school of medicine, as a professional school, has a duty to teach not only what to do, but why to do it. In other words, what is taught in medical school is not simply information-oriented, but also value-oriented.

Why history matters in medical education

As such, teaching history is an integral component of the curriculum. History helps us better understand our place in the world. It also helps us cope and work with the messiness and uncertainty inherent in the practice of medicine. Furthermore, it promotes skepticism—the idea that things change and all current innovations will at some point be surpassed. It clarifies the mutability of truth.

We have seen this countless times. One example is the use of a complex medicine (known as theriac) compounded from more than 30 ingredients, including the flesh or venom of vipers, believed to cure snakebite or other envenomation and later used in plague treatment during the Black Death. Another is the use of hepatica (liverwort), a flowering plant with a three-lobed leaf thought to resemble the lobes of the human liver and therefore, via the doctrine of signatures, considered a remedy for diseases of the liver. Yet another was the use of bloodletting, practiced for more than 2,000 years. Eventually all of these treatments were supplanted by discoveries of more effective ones.

Ironically, while these examples represent treatments that are no longer in use, some early concepts of good health have come full circle and become incorporated once more into our armamentarium, such as the ancient Greek concept of the six non-naturals: air; exercise and rest; sleep and waking; food and drink; repletion and excretion; and passions or emotions. All these were considered components of good health and have been reincorporated today into our ideas of lifestyle and environment as factors that contribute to health and illness.

A case study

For a detailed example, consider syphilis. This sexually transmitted disease is one that I frequently identify and treat in the Bronx at the Montefiore infectious disease clinic where I work. Its history has a great deal to teach medical students, not only about changing ideas of transmission and treatment, but also about the difficulties of diagnosis and the ethics of experimentation.

The latter refers, of course, to the Tuskegee Syphilis Study of African American males, sponsored by the Public Health Service of the United States and begun in 1932. This study was originally meant to examine the natural history of syphilis in those who had later stages of the disease. It was begun in a time before penicillin (introduced in 1943) was identified as an effective treatment and when there was considerable controversy about the efficacy of later-stage intervention. However, the study eventually spanned four decades, during which new treatments became available, and the subjects enrolled were often deliberately kept from receiving treatment.

Over time, it became clear that subjects were part of a vulnerable population not adequately protected by the study protocol and from whom true informed consent was not obtained. This troubling and complex story highlights the roles of race and racism in medicine and medical research, and has directly affected the structures we have in place for oversight of medical research today.

The routes of disease

Syphilis was first mentioned in European literature of the late 15th century. Like many other infectious diseases, it was initially associated with the movements of people; the Columbian hypothesis suggested that when Columbus returned from Hispaniola, his crew brought along the disease—a claim more recently supported by genetic analysis and a study of bone remodeling.

The condition also highlights the link between war and disease, since one of the ways it is thought to have spread across Europe was with the dispersal of Charles VIII’s mercenary troops after his ill-fated attempt to stake a controversial claim on the kingdom of Naples.

The importance of identifiers

Credit for coining the term “syphilis” goes to Girolamo Fracastoro, an Italian poet, mathematician and physician who wrote a poem called Syphilis, sive morbus gallicus, in which a shepherd of the same name is the first to be struck down by the disease after he angers the god Apollo. As the poem’s title suggests, people were in a hurry to place the blame for syphilis elsewhere. Disfiguring and ultimately fatal, syphilis was highly stigmatized. For instance, in France, it was called the Neapolitan disease; in Italy, the French disease (morbus gallicus). The Japanese called it the Chinese disease, and the Turkish called it the Christian disease. You get the idea.

In another, less fanciful book, Fracastoro identifies the concept of contagion, describing the person-to-person spread of “seeds of disease” nearly a century before the first microscope was invented.

Learning from historic treatment failures

Early treatments for syphilis such as mercury call into question the idea of how we gauge the efficacy of an intervention. In the absence of a microbiological understanding of disease, something worked if it produced a physiologic effect. There is no doubt that mercury, with its variety of toxicities ranging from excessive salivation to nerve and kidney damage, produced a notable effect. Even after syphilis was understood to be a bacterial illness—in fact, into the early 20th century—mercury was still in use as one of the remedies for syphilis. This may seem ridiculous now, but what doctors and scientists knew then about both mercury and syphilis meant that they were using the treatments that appeared, in their eyes at least, to provide the best outcomes.

Instead of such treatment being denigrated as outdated and harmful, perhaps it can serve as a reminder of our own relationship to healing, what we describe as cures and what we are willing to tolerate in order to find them. Our understanding and humility can give us perspective; one day medicine may regard our current treatments for syphilis (painful intramuscular injections or prolonged intravenous infusions of penicillin) and other conditions with the same disdain we hold for the administering of mercury.

Stories such as these, of syphilis or of the early microbiologists, prompt me to wonder how our current medical certainties will be regarded in a hundred years’ time. In the end, I am also comforted to know that people have struggled with most of the same human experiences throughout the ages and found within themselves, despite sometimes catastrophic circumstances, the capacity for resilience.