Editors’ Note: This month we began a series on promoting active learning in medical education. Every Tuesday in September, we’ve been highlighting a different aspect of collaborative learning. We’ve examined the importance of physical space, provided a framework for making large lectures more interactive and explored the benefits and components of team-based learning.

Today we explore the vital role that community service plays at Einstein in training future doctors.

by William B. Jordan, M.D., M.P.H. and Maria Teresa M. Santos, M.D.

“Is that the one with the ‘c’ on it? Or the pink pill? Or the number 10 pill?” One of our patients struggled to answer a question we had asked about his diabetes medicine. It was clear from his high blood sugar level, which was 400 ml/dl (the normal postmeal level is below 200 ml/dl), that he was having a hard time figuring out how to manage his diabetes.

This is not an uncommon scenario. When we talk with our patients in the clinic about medications or healthy habits to prevent or manage chronic illness, we frequently see expressions of confusion. Low health literacy makes it hard for some patients to cope with and successfully manage their medical conditions.

Most of the time, patients hide their confusion because they are embarrassed. It takes an aware and persistent healthcare provider to discover and manage low health literacy. As Dr. Mary Kelly so elegantly noted in her recent post on this blog, we have a health literacy crisis in the Bronx—and across the nation.

The frustration and vulnerability of patients such as the one mentioned above make it essential that we train future doctors to assess and address low health literacy. That is why the department of family and social medicine at Einstein makes health literacy a cornerstone of educating medical students.

In a voluntary program started by students in 2012, students work early in their medical school careers with patients in the community. The Patient Advocate Connection (PACt) is mentored jointly by family medicine and internal medicine faculty members within our department. The program involves about 10 percent of the first- and second-year classes. We connect pairs of students with primary care patients at our community health centers who have complex needs. Students start learning concretely, long before their third-year clerkships, how to address low health literacy.

Over 18 months, the student pairs connect with their patients by phone or in person about every two weeks. The students learn about the economic and social conditions that affect individual and group health, and help patients, most of whom have low health literacy, navigate a complex healthcare system.

PACt is just one of the ways students work together to improve health in the Bronx. Our core educational objectives for the required third-year clerkship in family medicine include communicating effectively with patients, families and communities, taking into account health literacy.

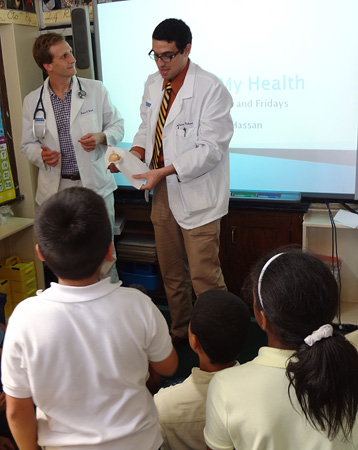

During the clerkship, students working in pairs complete projects at community sites. These sites range from a vocational day program for those with severe mental illness to community health center waiting rooms and public schools.

The students work with team members knowledgeable about health literacy to provide community-based health education. We provide our students with background information on health literacy and tools for addressing low-literacy audiences. The students put health literacy principles into practice by developing and delivering interactive one-on-one and group sessions on topics ranging from healthy eating to smoking cessation. The students then share their interventions with classmates and faculty members at the end of the clerkship.

As doctors we may not have time during 15-minute visits to communicate as well as we should. The clerkship stresses the importance of working as part of a team in a patient-centered medical home that includes partners—case managers and health educators—who can help overcome barriers such as health literacy. We also highlight the root causes of poor health and low health literacy, and how physicians engage publicly in systems issues that affect health.

How did our students help the patient with high blood sugar whom we mentioned earlier? Because the patient had limited reading skills, the students created a printout of his list of medications using only images and symbols, to remind him how many of which pills to take when. Following this intervention, the patient’s blood sugar levels improved. It is difficult to prove that the students’ actions led to the improvement. However, we can say with certainty that the patient was pleased with the additional information and support that the students offered.

Our work with students demonstrates how educators can align education with service to address the health challenges of society’s most vulnerable patients.

Comments on this entry are closed.