“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.” So wrote John Donne in 1642. While we might want to update this statement by saying “No person is an island,” and while this was intended to point out people’s dependencey on others, there is no more appropriate example of the application of this concept than infectious diseases, which have spread, unchecked, from continent to continent and neighborhood to neighborhood.

The epidemiologic concept of “one health” takes this further. One health holds that in addition to the epidemiologic connectedness of all people on earth, we are also connected, via infectious diseases, to many of the animal species we share the planet with. This reflects the expanded awareness that many diseases are transmitted from animals to humans; such diseases are known as zoonoses. Animals can transmit infections either directly to humans (rabies is an example) or via an insect vector, as with the mosquito-borne West Nile virus and the tick-borne Lyme disease.

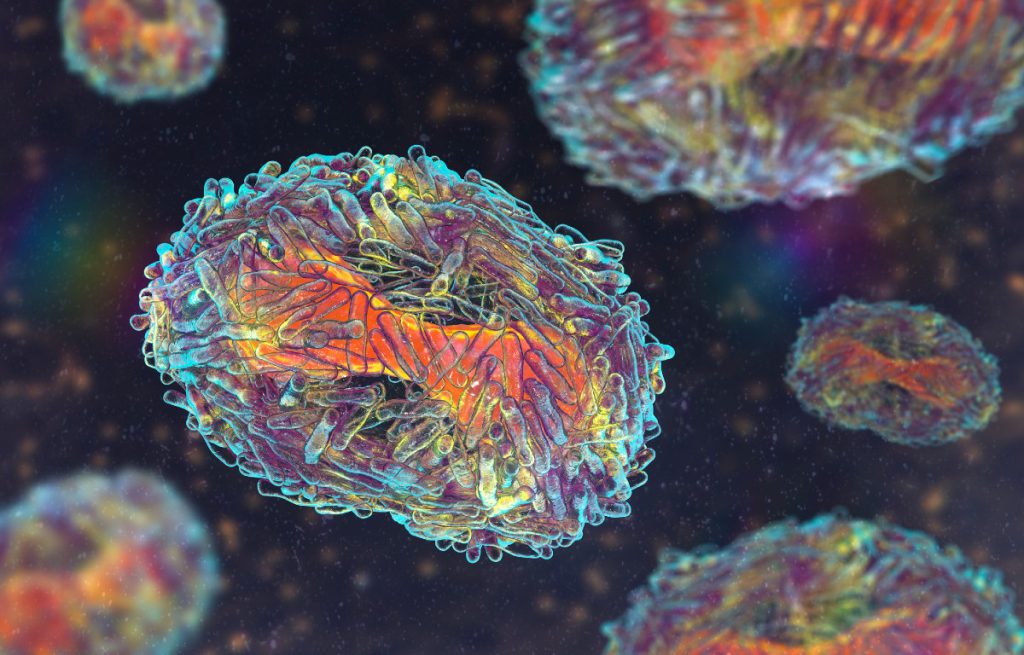

Now, while we are still grasping and grappling with the horror of a coronavirus pandemic, here comes monkeypox. This disease is caused by an orthopox virus similar to the one that causes smallpox. The name indicates that monkeys in central Africa may carry and transmit the disease, although species of African rodents are actually more-common causes of infection. Until 2003, when there was a minor outbreak of monkeypox in the United States due to human exposure to some exotic rodents imported here as pets, this disease was limited to the African continent. But that is changing rapidly. Several thousand cases have already been identified in the United States; New York City represents the epicenter of the disease in this country, with more than 1,100 cases. Last week, the New York State Commissioner of Health declared the virus an imminent threat to public health, a move intended to provide further resources to jurisdictions that have been most threatened by monkeypox. This follows the World Health Organization’s declaration of the virus as a global emergency. This feels like familiar territory. I hope we’ve learned some important lessons.

Fortunately, several factors make this outbreak far less potentially dangerous than COVID-19. One of the main differences is the method of contagion. While the SARS-CoV-2 virus is spread through respiration, making it highly contagious, transmission of the monkeypox virus is primarily through close and/or prolonged physical contact. This also differs from smallpox transmission, which can occur both by close contact and by respiration. In addition, persons born before 1972 will probably have received some smallpox vaccine, which may be somewhat protective. Because of the incredible success of smallpox eradication, routine smallpox vaccination was stopped at that time. Testing for monkeypox is increasingly available and should be performed in all suspected cases. A monkeypox vaccine (originally produced for smallpox protection) already exists; its safety and efficacy are known, and they allow for its rapid distribution and effective use. Drug treatment for those who have the disease also exists.

Despite the advantages inherent in the mode of virus transmission and potential protection by mass vaccination of target populations, the pox virus has already established a foothold in this country. The primary group infected has been the community of men who have sex with men. Presumably, this is related to unprotected sex with multiple partners allowing for spread. It is expected that the infection will be spread to women by bisexual men, and then forward to the heterosexual population. These facts call to mind the HIV/AIDS crisis, the fear and stigma surrounding it, and the suffering caused by society’s reluctance to tackle that disease. It’s a lesson many fear we have forgotten this time around.

The “Maybe Not” in this post’s title depends largely, if not entirely, on the rapid marshalling and administration of resources already available to thwart monkeypox. Vaccines must be urgently deployed to centers of infection without delay or imposition of political or economic restraints; education on the need for vaccination in target populations must be widespread and effective; personal protective equipment and appropriate isolation methods must be available and used; and antiviral agents must be available for proven cases.

These are all lessons that should have been well learned in dealing with HIV and COVID-19, and are absolutely essential if we are to truncate and contain this outbreak. If we fail at this effort, the answer to whether our experience with earlier viruses will be repeated—“Maybe Not”—will become “Certainly Will.”