Editors’ Note: The following post first appeared in the Official Blog of IJFAB: the International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics.

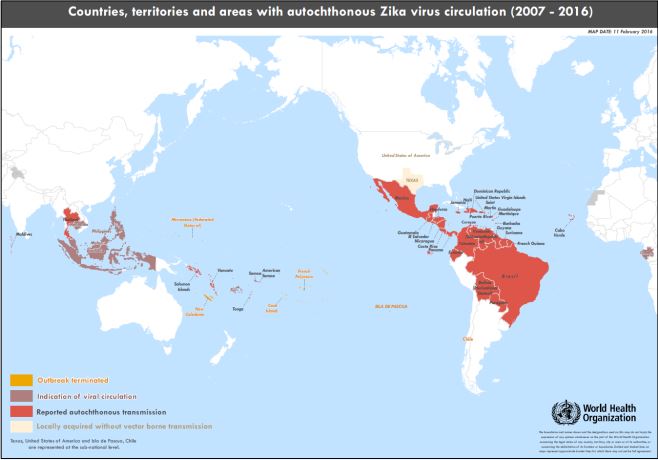

Global concerns about spread of the Zika virus continue to grow. More than 20 countries in Latin America–especially Brazil–as well as Caribbean locations and several states in the U.S. have reported confirmed or suspected cases. Yet, more remains unknown than known about the consequences of being infected with the virus. Although it is well-established that the virus is transmitted by the Aedes mosquito, it is unclear whether people can become infected through sexual contact with an infected person (one case in which the woman’s male partner had traveled abroad was reported in Texas), or by blood transfusions, even though the virus has been detected in blood, urine, semen, and saliva. The most devastating effect appears to be microcephaly (abnormally small head size) and accompanying brain damage of infants born to mothers infected with the virus, with thousands of cases in Brazil alone. Most recently, the virus has also been associated with eye abnormalities in affected infants. But even in those cases, scientists maintain that a causal connection has not been established. Another possible connection is Guillain-Barré syndrome, a condition that causes weakness and can develop into temporary paralysis.

Global concerns about spread of the Zika virus continue to grow. More than 20 countries in Latin America–especially Brazil–as well as Caribbean locations and several states in the U.S. have reported confirmed or suspected cases. Yet, more remains unknown than known about the consequences of being infected with the virus. Although it is well-established that the virus is transmitted by the Aedes mosquito, it is unclear whether people can become infected through sexual contact with an infected person (one case in which the woman’s male partner had traveled abroad was reported in Texas), or by blood transfusions, even though the virus has been detected in blood, urine, semen, and saliva. The most devastating effect appears to be microcephaly (abnormally small head size) and accompanying brain damage of infants born to mothers infected with the virus, with thousands of cases in Brazil alone. Most recently, the virus has also been associated with eye abnormalities in affected infants. But even in those cases, scientists maintain that a causal connection has not been established. Another possible connection is Guillain-Barré syndrome, a condition that causes weakness and can develop into temporary paralysis.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared the situation “a public health emergency of international concern.” This places WHO in the position of a global health coordinator in efforts to halt the spread of the disease, and also gives the organization’s decisions the force of international law. Even at this early stage, however, scientific research has been hampered by national laws such as one in Brazil that prohibits the transfer of human biological specimens to other countries.

So, what do public health officials recommend for people who may be exposed to the Zika virus? Despite the lingering uncertainty regarding a causal connection between infection in pregnant women and resulting microcephaly and brain damage in their infants, some ministries of health are recommending that women delay pregnancy. One such country is El Salvador, which has advised women to delay pregnancy until 2018. Men who have traveled to places where cases of the disease have been reported are urged to use condoms with their sexual partners. And, of course, all the obvious ways of preventing mosquitos from breeding are being recommended. Possibly the most hopeful approach is the release of genetically modified mosquitos that are altered to pass a lethal gene to their offspring, which die before they can reach adulthood.

Almost all of the countries in Latin America and the Caribbean that are most affected by Zika have strict abortion laws. El Salvador, for example, is one of five countries that prohibit abortion even to save the life of the woman. Although some people have called for loosening these restrictions in cases where pregnant women are infected, anti-abortion hard liners remain opposed. What should we make of the recommendations that women in those countries delay pregnancy and that men use condoms? If the HIV pandemic has taught us anything, it is that recommendations that men use condoms fall largely on deaf ears. And how are women supposed to “delay pregnancy” when they cannot negotiate sex with their male partners, when effective contraceptives are either unavailable or too costly, and where rapes are all too frequent? As a prominent feminist bioethicist wrote recently, “Asking women to avoid pregnancy without offering the necessary information, education, contraceptives or access to abortion is not a reasonable health policy.”

One of the most critical needs during a disease outbreak like Zika infection is international collaboration among scientists, including sharing of human biological materials and data. Without recently acquired blood and tissue samples, scientists are hampered in their search for effective preventive and therapeutic interventions. Brazil–the country with the largest number of Zika infections–has a strict biosecurity law that prohibits sending samples to other countries. According to one report, “Brazil has so far probably shared fewer than 20 samples when experts say hundreds or thousands of samples are needed to track the virus’ evolution and develop accurate diagnostics and effective drugs and vaccines. Many countries’ national laboratories are relying on older strains from outbreaks in the Pacific and Africa.” However, the most recent news suggests that the Brazilian government is considering a decree that would reform the current biosecurity law.

One reason countries like Brazil have enacted laws that prohibit sharing of biological materials is that commercial products later derived from such samples are costly and often become available in wealthy countries, but not in developing countries where the samples originated. Clearly, what is needed are enforceable international agreements for benefit sharing. One can only hope that in its role as global health coordinator in the Zika epidemic, WHO will have the foresight and authority to urge reforms in the current barriers to cross-border sharing of biological materials and any resulting commercial benefits.