Editors’ Note: This summer, six students from Albert Einstein College of Medicine have traveled to Soroti, Uganda, to treat diabetes as part of Einstein’s Global Diabetes Institute (GDI). During this period, we will run a series of posts detailing their challenges and progress. In this post, second-year M.D. student Jeannie Tran shares her thoughts about medical care in Soroti. The trip was funded by Einstein’s Global Health Fellowship Program.

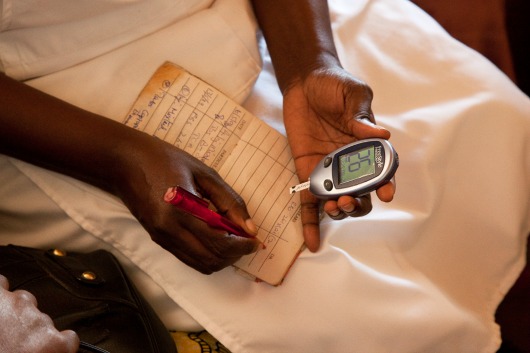

Photo Courtesy of Gary Goldenberg

Having never traveled outside the U.S. before and having only just finished my first year of medical school, I was nervous about going abroad under the auspices of the GDI to work at Soroti Regional Referral Hospital (SRRH), a facility with few resources and a patient population whose primary language I do not understand. To my surprise, the adjustment has not been too difficult. The lack of medical resources that initially seemed to be a drawback at SRRH is, in fact, eased by a collaborative hospital staff and a team of physicians with impressively widespread knowledge and skills.

We spent our first week familiarizing ourselves with the hospital, attending rounds, assisting at the hospital’s diabetes and hypertension clinics and meeting with doctors and administrators to implement our three main projects: data collection, education and a prosthetics workshop. Prior to arriving, I imagined that the hospital here could provide little for its patients. In my first year of medical school, I became accustomed to physicians who are experts in a certain segment of medicine, and to hospital care that requires the use of expensive machinery. SRRH has neither of these. Instead, it has physicians with expert knowledge that extends beyond their own specialties, who are capable of treating numerous patients based on physical examinations alone.

Though I am constantly impressed by the doctors I encounter in the U.S., I am even more impressed by the doctors I have met here. SRRH would benefit greatly if it had more resources. It lacks even the most basic supplies that many of us in the U.S. medical field may take for granted, such as clean note-taking paper. Despite these challenges, the doctors here have created a system of care that employs creative improvisation. For instance, during a surgical round, the doctors used a bag of water as a weight to help lengthen a fractured bone to ensure that the bone would heal correctly.

Consequently, as a medical student in her preclinical years, I have learned much more here in one week than I would have if I had spent the same amount of time in a U.S. hospital. Not a single medical question has been asked that a doctor has not been able to answer, and in many ways, it feels as if each physician here is an internist, a cardiologist, a pediatrician and so on, all in one.

After my first week, I was filled with awe and appreciation for the more raw aspects of medicine that we rarely see in hospitals in the U.S, and I cannot help thinking how amazing care here would be if SRRH had more basic resources, such as space. For instance, I have observed patient beds in the internal medicine ward literally touching each other because there is no other location to see patients, and it is incredibly disheartening to watch competent medical professionals not be able to treat patients simply because those professionals don’t have the means.

Overall, I don’t believe that one type of care (care in the U.S. or care here in Soroti) is better than the other. Rather, I believe that both have invaluable qualities to offer and that an integration of the two would be ideal. For the next few weeks—and, I hope, for years—our Einstein team under the auspices of the Global Diabetes Institute will promote and facilitate such integration at SRRH. I am excited to have the opportunity to be a part of this burgeoning partnership.