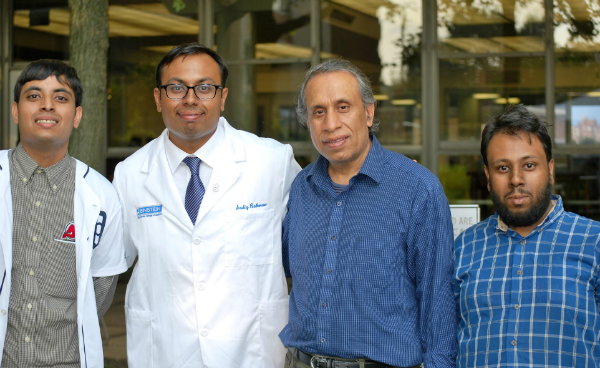

From left to right, Sadaab (my youngest brother), my dad Ashraf, and younger brother Sadat

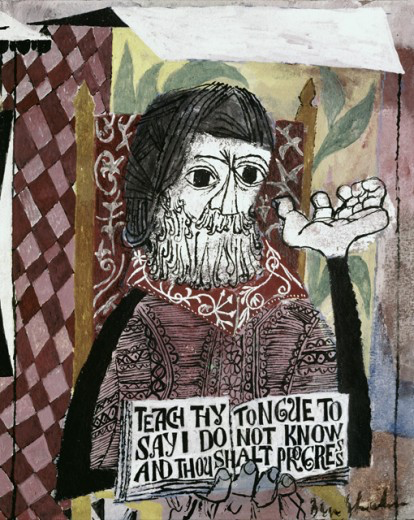

In my eight months at Einstein, I’ve often been struck by a painting of Maimonides on campus. The artwork features him holding pages of a book that say, “Teach thy tongue to say I do not know and thou shalt progress.”

That quote resonates with me more each day. As a first-year M.D. student, I’ve uttered the words “I don’t know” much more than ever. I’ve discovered that, whether I’m naming nerves found in the infratemporal fossa during anatomy observations or coming up with differential diagnoses for a healthy young woman who came into the emergency department with shortness of breath, medical school humbles you quickly.

I’ve been trying to feel less uncomfortable about this and have started using these moments to patch gaps in my knowledge. Hearing the words “I don’t know” from a physician recently stirred up a host of emotions in me, not because of my experiences at medical school but because of my personal experiences with the medical profession at home.

I’ve been trying to feel less uncomfortable about this and have started using these moments to patch gaps in my knowledge. Hearing the words “I don’t know” from a physician recently stirred up a host of emotions in me, not because of my experiences at medical school but because of my personal experiences with the medical profession at home.

This year brought new and unexpected challenges to my family. On New Year’s Day, I was at home in Queens, New York, contemplating how relaxing and “boring” winter vacation was while I looked forward to classes starting up again. That evening, everything changed. I heard my younger brother, Sadaab, cry for help and alert us that he was about to fall as he exited the bathroom. My father and I quickly rushed to grab him as he lost consciousness, collapsing into our arms.

My brother suffers from a pain condition called complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). We had never seen anything like this happen to him before. After a few minutes, he was able to hear us and drink some fluids but wasn’t able to open his eyes or stay seated for long. Years of experience with his CRPS made us hesitant to go to the emergency department. As weird as that sounds for a medical student to say, EDs are notorious within the chronic-pain patient community for not having the knowledge needed to deal with those episodes.

This time we had no choice. Riding in the back of the ambulance with my brother, I observed him wincing in pain with every bump in the road. Despite the discomfort, he was able to answer all of the emergency medical technician’s questions, and to thank her for her help. At our local ED, my brother repeated the medical history he has recited hundreds of times in the past. To that list he added the symptom he felt prior to his episode of syncope: a rapid surge in heart rate. In the early morning, after receiving a couple of bags of intravenous fluid, he was able to open his eyes, but his heart rate was still elevated. An electrocardiogram (EKG), urine sample, and blood sample all came back negative, though, and the attending told us that there was no definitive diagnosis for my brother. He recommended we follow up with Sadaab’s neurologist. Basically, the hospital staff didn’t know what was wrong.

Back at home, we discovered that Sadaab’s balance issues―which had eased with treatment, allowing him to use a cane for walking―had returned, forcing him back into steadying himself using the walker he’d previously ditched.

The neurologist said my brother’s symptoms were mainly cardiovascular. We were advised to see a cardiologist.

After another EKG as well as an echocardiogram, structural abnormalities of my brother’s heart were ruled out. His cardiologist still wasn’t able to provide him with any answers or medication to help alleviate his symptoms. So, after a week when his heart was monitored, the results came back―you guessed it―normal. The cardiologist said he shared our frustration, adding that the symptoms were most likely due to an autonomic neuropathy affecting the nerves to my brother’s heart, resembling conditions such as POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome).

POTS’ symptoms of resting tachycardia and blood pressure plummeting when standing (leading to dizziness and fainting) certainly matched my brother’s experience. Unfortunately, physicians don’t know what causes POTS or have any effective treatments for it, other than prescribing medicine to elevate blood pressure.

Still, the doctor couldn’t say it was POTS. I was annoyed. Sadaab was once again relegated to being a medical mystery, instead of being able to live the life of a normal 21-year-old college student. What I appreciated, however, was how the physician admitted he didn’t know exactly what was wrong with my brother.

Five years earlier, when he was first diagnosed with CRPS, we didn’t know much about it. After a host of exams he was transferred to a rehabilitation hospital in Manhattan to complete inpatient physical therapy and to receive help in regaining mobility in his left leg, which had been affected by incredible pain.

The pain remained, but the physician in charge of his care assured us that previous patients with CRPS had responded well to therapy. She seemed to confident in this, and we were glad.

However, an accident soon after Sadaab returned home made matters worse. The physician who’d previously expressed confidence about my brother’s recovery now suggested that the pain was inside my brother’s mind. We thought this was ludicrous, but Sadaab followed through with therapy. After multiple sessions, it was determined that my brother’s pain had no psychological basis.

For the next year, the pain and tremors continued and my brother’s condition deteriorated. After Sadaab switched physicians and started a new pain-management regimen, his pain levels decreased. With this latest episode he is again fighting to learn how to walk without an assistive device.

Observing his new struggles has helped me come to terms with the phrase “I don’t know.” The intensity of emotions that patients and their families experience is so strong that I’m determined not to pretend to know the answer to a question or diagnosis and add to their frustration. I want to be the type of doctor who will seek answers myself―or find colleagues with the answers. I want to be the type of physician who’ll admit when there isn’t a good answer. Most of all, as I train to become the M.D. that I would want for patients like my brother, I will keep in mind the power and importance of the words “I don’t know.”