The front-page New York Times article, “A Mysterious Infection, Spanning the Globe in a Climate of Secrecy” and its companion pieces, “Candida Auris: The Fungus Nobody Wants to Talk About” and “Culture of Secrecy Shields Hospitals With Outbreaks of Drug-Resistant Infections” have sparked a lot of important conversations and concern about a fungus that has surprised many with its rapid global spread and its high frequency of drug resistance.

The front-page New York Times article, “A Mysterious Infection, Spanning the Globe in a Climate of Secrecy” and its companion pieces, “Candida Auris: The Fungus Nobody Wants to Talk About” and “Culture of Secrecy Shields Hospitals With Outbreaks of Drug-Resistant Infections” have sparked a lot of important conversations and concern about a fungus that has surprised many with its rapid global spread and its high frequency of drug resistance.

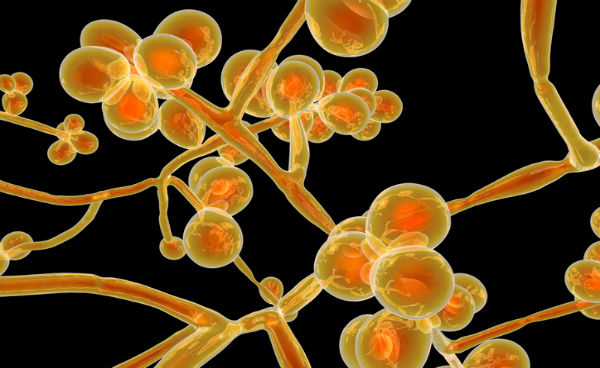

Because this fungal infection is little known to the general public, has the ability to escape detection, and is difficult to treat, it makes for compelling reading in the Times. Highlighting the dangers of this remarkable pathogen can be helpful, but it is disingenuous to suggest that “no one wants to talk about” C. auris or that it’s a “secret”—and that’s why it’s important to understand what we’ve learned so far.

A Decade of Conversations

In the 10 years since its discovery, there has actually been quite a bit of conversation among healthcare specialists and government workers about C. auris and what needs to be done about it. The medical press has even covered these meetings. In 2017, for example, I coordinated a symposium on C. auris at IDWeek, the premier meeting for infectious diseases specialists in the U.S. At that meeting, Tom Chiller, the chief of the Mycotic Disease Branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), spoke in detail about the fungus. That was followed by another C. auris symposium at the 2018 IDWeek, which I also coordinated. We will once again gather at IDWeek for several talks about C. auris in October of this year. Similarly, ASM Microbe, the premier microbiology conference in the U.S., has had numerous talks on the fungus since 2017. These activities and others have provided important forums for educating physicians, scientists, and the community about efforts to enhance the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of C. auris infections.

The CDC has certainly done its share of communicating about C. auris, giving it a significant online presence through the center’s dedicated, frequently updated webpage. This site was set up to provide detailed information for the public as well as for health professionals.

Taking Local Action

New York state health authorities have also been talking about the pathogen. New York has unfortunately borne the brunt of the U.S. epidemic, with over 300 cases confirmed to date. Statewide, infectious diseases experts and public health workers, including members of the faculty of Albert Einstein College of Medicine, have been working hard to inform the medical community about the dangers of C. auris. Those efforts are missing from the Times coverage. The New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) has an up-to-date webpage for the fungus, providing specific prevention and treatment recommendations aimed at the public and at health professionals. The department has also released numerous publicly available health bulletins.

In my view, the NYSDOH, the New York City Department of Health, the CDC, and health departments in other states are all working together in earnest to address the C. auris scourge. At Montefiore, Einstein’s University Hospital, members of our infection-control staff have been actively surveilling for C. auris and have rigorous programs in place to combat the fungus.

And the fight against C. auris is indeed global. My fellow mycology investigators are exploring various aspects of the pathobiology of the fungus. This work has been greatly facilitated by our vast knowledge regarding other pathogenic Candida species. I’ve had a hand in this effort, too, as my laboratory has identified differential regulations of drug-resistance pathways in C. auris isolates that are susceptible or resistant to antifungal medications. We have also found that antifungal-drug exposure alters various activities, such as the loading and release of extracellular vesicles from C. auris.

Still, it’s important that the story of C. auris has caught the eye of the mainstream press. The public should know about the danger of this pathogen, as well as what can be done to help prevent its spread. As new findings become disseminated through publicly available peer-reviewed journals, infectious diseases researchers will be doing our best to inform the public about what makes C. auris tick and what we as healthcare professionals, scientists, and community members can do to combat the spread of this and other infectious microbes.

Comments on this entry are closed.

Dr. Nosanchuk’s blog post is most informative and succeeds in rebutting the claim in New York Times articles that “no one wants to talk about” C. auris or that it’s a “secret.” However, the blog post does not discuss one important feature noted in the Times articles: “…hospitals and nursing homes have been unwilling to disclose outbreaks or discuss cases….States have kept confidential the locations of hospitals where outbreaks have occurred, citing patient confidentiality and a risk of unnecessarily scaring the public.” (Matt Richtel, “A Mysterious Fungus Attacks a Mother of 4, and Doctors Are Powerless to Stop It,” April 18, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/17/health/candida-auris-fungus-chicago.html). Preserving patient confidentiality is an important ethical consideration, and I fully accept that justification for secrecy. But what about “unnecessarily scaring the public”? Does the public have a “right to know” the location of hospitals and nursing homes where cases of C. auris have occurred? Clearly, those healthcare facilities have a self-interested reason to avoid unfavorable publicity. The public has a countervailing interest in avoiding what Dr. Nosanchuk refers to as “the C. auris scourge.” Protecting patient confidentiality is a justifiable defense of secrecy. The paternalistic reason–“a risk of unnecessarily scaring the public”–is not ethically defensible.

We don’t seem to be having any trouble with hearing about the measle outbreak daily. It’s very interesting that we can’t find out which facilitates have the Candida auris.