Headlines are pouring in, warning us of the impending spikes in coronavirus cases throughout the country and the rise of eerily disturbing cases of children with a mysterious viral rash. All of these alerts appear against the backdrop of the loudest national outcry for justice and equality since the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Headlines are pouring in, warning us of the impending spikes in coronavirus cases throughout the country and the rise of eerily disturbing cases of children with a mysterious viral rash. All of these alerts appear against the backdrop of the loudest national outcry for justice and equality since the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Navigating these crises is exhausting, given the dual existence experienced by many Black and Latinx physicians around the nation. We overwhelmingly care for vulnerable, underserved communities while repressing personal wounds from the pandemic and civil disenfranchisement. These are my concerns, and I wonder—in the moments between telemedicine calls, research, and patient visits—who is taking care of the minority physicians?

Physician burnout is a real problem for all doctors, and these stresses cost U.S. healthcare systems roughly $4.6 billion annually in turnover, in lost physician productivity, and, worst of all, in the harm to patient care, careers destroyed, and M.D. lives lost. Now imagine personally taking in the firehose of news about COVID-19 and the fight for racial justice. On a personal level, that news triggers my own sadness at recently losing my uncle to the COVID-19 wave. But I also have fear, closely accompanied by anger, because I do not know what is more threatening to my godson’s life—a virus or a police officer.

And yet dwelling on these topics is actually a luxury, because it at least distracts from the demands of practicing medicine and managing the growing needs of a fresh class of interns in the hospital. These days, I return home to commiserate with my husband—a nurse in a Bronx psychiatric emergency department, combating the silent epidemic of mental illness. As Black healthcare professionals, we understand the additional burdens of each day, and prepare to start the marathon again the following morning.

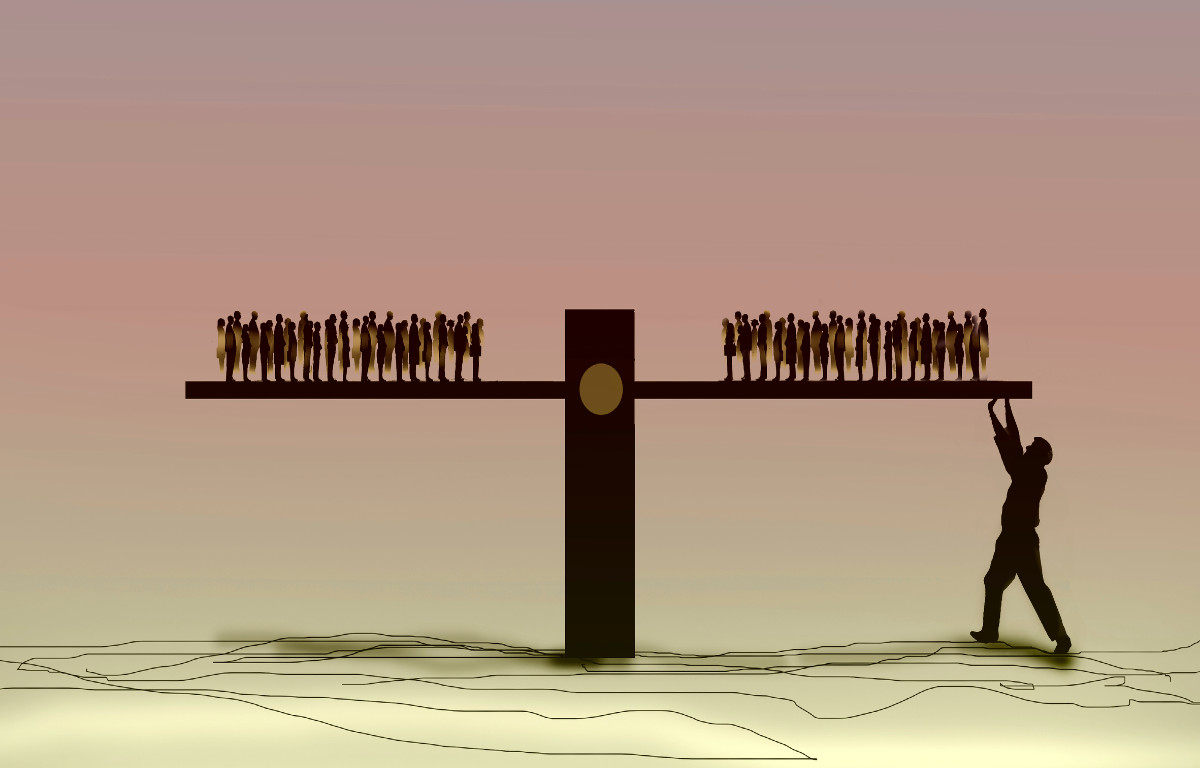

Unique to physicians underrepresented in medicine (URM) is the position of being in close proximity to vulnerable communities in our professional and personal lives. Based on anecdotal evidence, I believe this is increasing the risk of burnout for all of us. According to the most-recent physician workforce data, only 4.8% and 6.0% of the total physician workforce are Black/African American or Latinx, respectively. Self-reported data show that these same physicians are choosing to work in underserved, typically urban communities.

This distribution of URM physicians places them in the direct path of the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic. Burnout is further exacerbated by the continual strain that is placed on our relationships with our patients and our own families. The vast majority of our patients are categorized by society as essential workers, retail or restaurant workers, or those who have recently become unemployed. The pandemic has spurred a growing demand for their physicians to provide disability forms, exemptions from high-risk work environments, and referrals to community programs to address housing and food insecurity. This has also resulted in an increased struggle for URM primary care physicians, who overwhelmingly provide care for this patient demographic, to complete administrative tasks. These same physicians often are first-generation healthcare professionals, who go home to act as health advocates and proxies for their loved ones, managing the paperwork necessary for their survival.

Coronavirus has thrust our nation into a downward economic spiral that is harming every major industry, including healthcare. Numerous hospitals across the nation are scrambling to address the major budget deficits left in the wake of the pandemic, while others close their doors permanently. Many of these institutions are built on a capitalistic framework, generating a majority of their revenue from elective surgical procedures. However, due to the tenuous reopening of urban centers, many of these departments are not fully operational. As a result, URM physicians have either increased patient panels with shorter visit times or, conversely, not many patients at all in their surgical practices. Carefully nurtured therapeutic bonds developed with patients as they managed their diabetes or prepared for knee-replacement surgery after battling years of arthritic pain have vanished overnight.

Our families do their best to support us during these perilous times. However, that support is often limited by these same stresses. I’ve witnessed many of my colleagues enduring the emotional challenges that come with social distancing from parents and grandparents—key traditional sources of support. Furthermore, we are all too aware of the “preexisting conditions” plaguing Black and Brown communities, and live with the knowledge that our loved ones are not exempt from those dangers. There is the additional angst we live with in knowing that our parents and loved ones often need to work at grocery stores or take public transportation to provide for themselves.

The Brookings Institute reports that the age-adjusted death rates for Black and Hispanic/Latinx people are 3.6 and 2.5 times higher, respectively, than for whites. One way that leaders of healthcare institutions can help mitigate this angst is by allowing temporary expansion of health coverage to URM physician family members. They can also use their influence in organizations such as the American Medical Association to lobby for a national healthcare system.

Now that the pandemic has seemingly settled to a lull in New York and several other states, institutions there can use this time to fortify their diversity, equity, and inclusion infrastructures. Department and division leaders have the cost-free authority to commission task forces to reexamine current institutional policy to insure against racism. They can also generate reading lists of antiracist literature and the history of the discriminatory health policies that contributed to the disparities we are witnessing during this pandemic for their staffs. These interventions are a step forward in cultivating a work environment of support for physicians weary from the ongoing battles being fought at the bedside and at home.

Here’s the reality: Our challenges are seemingly innumerable, and are compounded by the explicit demonstrations of racist acts and vitriol in society. For underrepresented doctors, our dual existence in society must be recognized within our profession, and leadership must seize this moment to reimagine how to support us. A concerted focus on how to alleviate burnout in our physician demographic should lead to practices that alleviate burnout for all in the profession. Whether through advocacy for expanded healthcare access/infrastructure, creation of inclusive work environments to mitigate microaggressions, or development of antiracist curricula to empower non-URM physicians to practice structurally competent care, leadership must first ask the essential question—who is taking care of the minority physicians?